Editor's Note

The Quartz Crisis stands as the most pivotal chapter in modern horological history—a story so rich with drama, innovation, and human resilience that it demands the space to breathe. Rather than compress this epic into a single overwhelming read, we've divided it into two complementary parts.

Part I chronicles the fall: how Swiss complacency and Japanese ambition combined to nearly destroy an industry that had thrived for centuries. Part II reveals the resurrection: the unlikely heroes, radical strategies, and stubborn acts of faith that pulled mechanical watchmaking back from the brink.

Together, they tell the complete story of how the watch industry learned that survival sometimes requires losing everything first.

Part I – The Fall

The Birth of an Idea

The story of the Quartz Crisis doesn't begin in Tokyo, as many assume. It begins in Switzerland, in the quiet lakeside town of Neuchâtel, where a consortium of nearly twenty watch companies founded the Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH) in 1962. Their mission was audacious: miniaturize the quartz oscillators—bulky laboratory instruments used since the 1920s—into something slim enough for the wrist.

Seven years later, in 1969, CEH unveiled the Beta 21 quartz movement. It was a chunky, humming marvel that beat with unerring precision at 8,192 vibrations per second—a revolution dressed in gold and launched through the most traditional channels: luxury maisons like Omega, Patek Philippe, Rolex, and IWC.

The Swiss made a fateful decision. Instead of locking the patents away, CEH chose to make the technology broadly available, assuming that collective strength would protect the nation's centuries-old dominance. If everyone has it, Switzerland cannot lose, was the thinking.

What they didn't count on was that others—especially in Japan—would scale it faster, cheaper, and with merciless efficiency.

A Christmas Earthquake

On December 25, 1969, as the world exchanged gifts, Seiko unwrapped a present that would change horology forever: the Quartz Astron 35SQ, the first commercially available quartz wristwatch.

It was an 18-carat gold beauty, priced at 450,000 yen—about the cost of a Toyota. The Astron was precise to within five seconds per month, roughly 100 times more accurate than the finest mechanical chronometers of the era.

If CEH invented the movement, Seiko democratized the future. The Astron was proof that quartz was no longer a laboratory experiment or Swiss curiosity. It was tomorrow, and tomorrow had arrived.

At first, quartz remained a luxury. Patek Philippe's Beta-21 powered Ref. 3587 came in hulking gold cases that looked like props from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rolex's "Texan" (Ref. 5100) sold out quickly and became the company's most expensive offering. Collectors today still marvel at their audacity—and their astronomical prices when they originally came out.

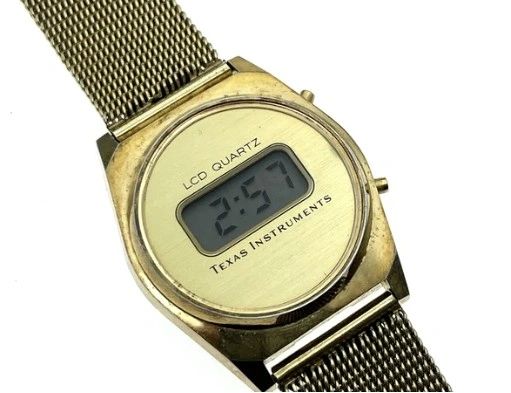

But by the mid-1970s, competition from outside Switzerland drove prices down drastically. Semiconductor makers like Texas Instruments from the U.S. began producing digital quartz watches by the millions. In 1976, TI offered a quartz LED watch for $19.95. By the following year: $9.95.

Suddenly, a watch was no longer a treasured heirloom passed from father to son. It was a gadget, sold at the checkout counter of a supermarket. Watches became so cheap that consumers would not even bother replacing the battery once it died, they'd simply replace the whole watch.

The Silent Valleys

For Switzerland, the consequences were nothing short of catastrophic. In 1970, the Swiss watch industry employed nearly 90,000 people across 1,600 companies. By the mid-1980s, the workforce had withered to just 28,000, and only 600 companies remained.

In the Jura mountains, villages that had thrived for generations on the rhythm of balance wheels and escapements fell silent. Factories shuttered. Young apprentices abandoned their benches. The proud words "Swiss Made" began to sound like epitaphs from a dying era.

Enicar, once celebrated for its Sherpa Graph chronographs and Himalayan expeditions, declared bankruptcy in 1987. The machinery was auctioned off, the name reduced to a dormant trademark. It was a quiet, devastating end to a brand that had once epitomized Swiss tool-watch excellence.

Across the Atlantic, the American watch industry fell even faster—and harder. Elgin, once the world's largest watchmaker, closed its final U.S. plant in 1968, just as quartz was emerging. Hamilton, another pillar of American horology, was absorbed by Swiss groups in 1974. Benrus, supplier of military timepieces to the U.S. armed forces, filed for bankruptcy in 1977.

Factories that once produced millions of mechanical movements stood empty. Skilled craftsmen retrained or drifted away. A century of American watchmaking vanished almost overnight, leaving barely a trace.

The statistics still sting. Between 1970 and 1985, Switzerland's global market share plummeted from 50% to under 15%. Entire segments vanished, particularly the affordable mechanical watches that had served everyday buyers for generations.

The watch—once a symbol of craftsmanship, precision, and pride—had been reduced to a disposable trinket. Swiss watchmakers who had spent lifetimes regulating balance wheels and hand-polishing bridges suddenly found their skills obsolete, their knowledge worthless.

The Gathering Darkness

By the early 1980s, the mood was somber. Trade publications filled with obituaries for beloved brands and lamentations about the end of centuries-old traditions. Apprenticeships dwindled. Parents urged their children to find different trades.

At watch fairs, the excitement belonged to Japanese and American brands displaying cheap quartz digitals with alarms, calculators, and flashing LEDs. Swiss booths felt like ghost towns, populated by aging men selling relics to an indifferent world.

The unthinkable had happened: the masters of timekeeping had been dethroned—not by superior mechanics, but by a cheap crystal and a battery.

Last words

The Quartz Crisis was not a single catastrophic event but a slow, grinding collapse. It was a story of brilliance undone by complacency, of revolutionary innovation that slipped through the fingers of those who created it. By the mid-1980s, Switzerland was on its knees, and most observers believed it would never rise again.

But history, like time itself, is full of surprises. In the ruins of shuttered factories and silent valleys, a few stubborn souls refused to surrender. And from those embers would come the most improbable revival in the history of luxury goods.

Next time, in Part II: The heroes who defied management, the plastic watch that saved Switzerland, and how the mechanical heartbeat returned stronger than ever.

Article prepared by Omar, Founder at The Watch Curators.