How one man’s belief in artistry, storytelling, and uncompromising quality changed the future of watches forever.

How it all began

If you’re into watches, you’ve certainly heard of the “Quartz Crisis.” It was the tsunami that struck the Swiss and German watch industries in the 1970s and 1980s, triggered by the invention (ironically by the Swiss themselves) and mass production of inexpensive quartz watches, especially from Japan, with Seiko leading the charge. Quartz technology was far more accurate, affordable, and easier to produce than traditional mechanical movements.

For an industry that had built its reputation on the promise of “the most precise watches in the world,” quartz timepieces were an existential threat. A battery-powered quartz movement beats at a frequency of 32,768 Hz, while a standard mechanical watch oscillates at just 2.5 to 3 Hz. The difference was staggering.

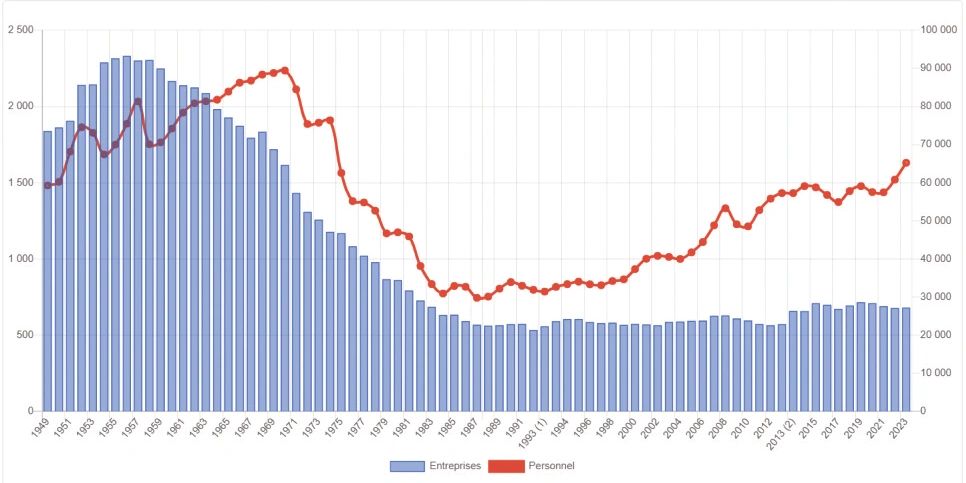

Global demand for mechanical watches collapsed. Dozens of historic Swiss brands went bankrupt, and employment in the watch industry fell from around 90,000 in 1970 to barely 25,000 by the mid-1980s. Generations of watchmakers, engravers, enamellers, and other artisans were forced to abandon their family heritage and seek work elsewhere.

Amid the rubble, however, two men—neither Swiss, and neither with family roots in the métier—worked in parallel to revive this seemingly condemned part of the Swiss soul. The more famous was Nicolas Hayek, the Lebanese entrepreneur behind the Swatch brand and the Swatch Group. The other, whose story we want to tell, was a German engineer from Nuremberg. His name was Günter Blümlein, and some of today’s most influential figures in the industry regard him as a mentor. These include Jérôme Lambert, Richard Habring, and Maximilian Büsser.

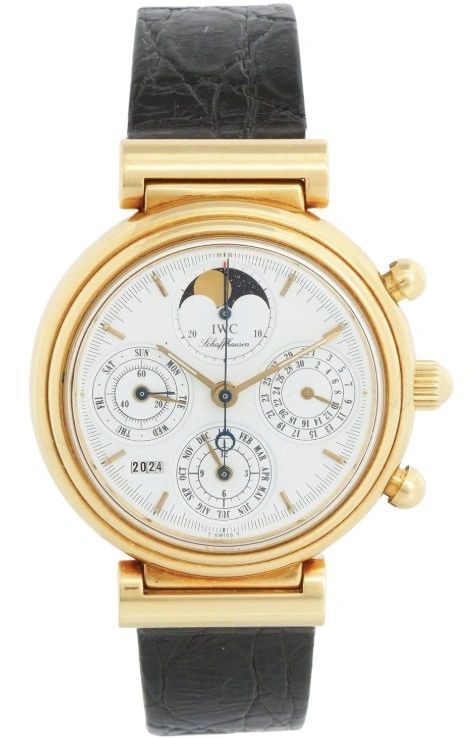

If you’ve ever admired the quiet poetry of a Lange 1, the confident complexity of an IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Chronograph, or the timeless elegance of a Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso, you’ve glimpsed the Blümlein vision.

From Nuremberg to Glashütte: An Outsider Enters the Stage

Born in Nuremberg in 1943, Blümlein was a child of a Germany still in ruins, a nation divided, rebuilding its industries and its identity from scratch. Unlike many of the grandees of Swiss horology, he had no inherited ties to watchmaking in Le Locle or Geneva. Instead, he studied fine mechanics at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, where the focus was on precision instruments, optics, and engineering rigor—disciplines that were absolutely necessary for the painful and long rebuilding of the German nation. These were also the elements that would later give him a sharper, more pragmatic edge than his Swiss contemporaries.

His entry into watchmaking was almost accidental. He joined the electronics group Diehl, which at the time owned Junghans, then the world’s largest watch manufacturer by volume. It was there that Blümlein received his real apprenticeship—not at a watchmaker’s bench, but inside the machinery of a modern industrial group. At Junghans he saw the clash of tradition and technology up close: mass production techniques on one side, centuries-old craft on the other. He absorbed not only the discipline of engineering and industrial process but also something rarer—the importance of marketing, distribution, and above all, storytelling in giving technical products emotional value.

That combination—precision plus narrative—would become the foundation of his genius approach, enabling him to rescue brands from collapse and reframe mechanical watchmaking as both an art and a cultural treasure.

Quartz May Have Won the Battle, But Not the War

By the early 1980s, mechanical watches looked obsolete. Quartz was cheaper, more accurate, and modern. Yet Blümlein grasped something others missed: accuracy was no longer the point.

A mechanical watch could never outpace a Seiko in timekeeping, but it could offer something quartz would not: heritage, emotion, and artistry. Nobody would ever boast of inheriting a Casio from their great-grandfather, nor imagine passing down a plastic quartz watch to their own grandchildren 50 or 60 years later. Mechanical watches carried stories: the engraver’s hand on a balance cock, the rhythm of a movement that echoed the human heartbeat, the patina of decades. This deep emotional dimension was the one edge left to play—and Blümlein recognized it sooner than almost anyone else.

In 1982, he was chosen to run Les Manufactures Horlogères (LMH), a new holding company created by the German group VDO, which at the time was best known for its car instrument panels. VDO saw potential in owning prestigious but struggling Swiss watch brands, but they needed someone with both engineering rigor and business acumen to rebuild them. Blümlein, with his Junghans experience and rare ability to bridge precision mechanics and storytelling, was the obvious choice. LMH included IWC and, soon after, Jaeger-LeCoultre—storied houses reduced to survival mode in a quartz-dominated world. His mission was as audacious as it was improbable: to reinvent them for a generation that thought it no longer needed mechanical watches—and to prove that tradition, reimagined with intelligence and vision, could still shape the future.

IWC: The Engineer’s Spirit

At IWC, Blümlein found kindred souls. He knew how to encourage bold experiments: some of those innovations include the use of titanium cases (a first in the industry), ceramic watches, and most famously, the development of the Da Vinci Perpetual Chronograph. Developed with Kurt Klaus’s ingenious perpetual calendar module, it could be adjusted entirely through the crown—an engineering feat disguised as elegance.

And then there was IWC Porsche Design—sleek, functional, and effortlessly cool in the way only the 1980s could be. These watches signaled that IWC wasn’t afraid to embrace modernity. Under Blümlein, the brand leaned into its identity as the “watchmaker for engineers”—not aristocratic, not nostalgic, but innovative, masculine, precise.

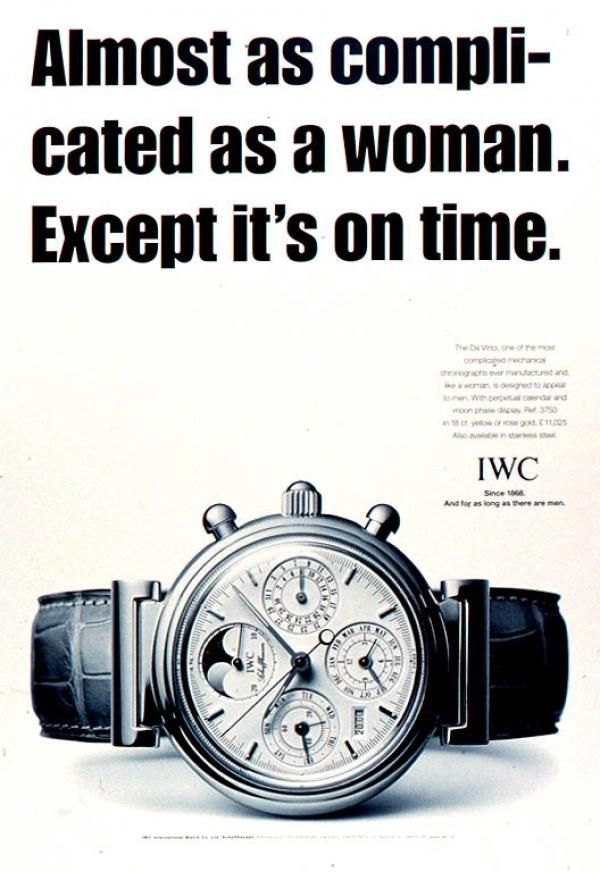

By the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, IWC grew increasingly comfortable pushing boundaries—not only in watchmaking but also in its messaging. Genuinely provocative campaigns, created by the Zurich-based agency Wirz Werbung under Blümlein’s leadership, carried daring taglines like “Almost as complicated…” These ads cemented IWC’s edgy, unapologetic voice and gave the brand a distinctive swagger in an otherwise conservative industry.

That positioning still resonates today—every time someone straps on a Portugieser or Pilot’s Watch, they’re wearing more than a timepiece; they’re wearing the legacy of a brand that wasn’t afraid to break the mold.

Jaeger-LeCoultre: The Sleeping Giant

If IWC was about engineering bravado, Jaeger-LeCoultre was about depth. For decades, JLC had been the industry’s “watchmaker’s watchmaker,” quietly supplying movements to the very best—Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Vacheron Constantin—while rarely putting its own name in the spotlight. The maison had the know-how, but not the recognition.

Blümlein changed that. He understood that JLC’s true strength lay in its unrivaled technical library—more than a thousand calibres developed over its history, a breadth no other manufacture could match. He pushed the brand to celebrate this mastery rather than hide it. Under his guidance, the Reverso was not just revived but reimagined, transforming from a charming 1930s polo watch into a versatile 1990s design icon, a canvas for complications and artistry alike.

At the same time, Blümlein encouraged bold horological statements. The Grand Réveil, a perpetual calendar with alarm, epitomized JLC’s ability to combine mechanical ingenuity with practical complexity—proof that the maison could not only support others but lead innovation in its own right.

By insisting JLC step out from the shadows and celebrate its brilliance, Blümlein elevated the brand from a discreet supplier’s workshop to a pillar of haute horlogerie, restoring it to the stature it deserved among the great maisons of Switzerland.

A. Lange & Söhne: When Time Came Home

But Blümlein’s greatest masterstroke came in the early 1990s, east of the Iron Curtain. In Glashütte, the historic German brand A. Lange & Söhne had been wiped off the map by the German Democratic Republic, its workshops nationalized, its name erased from dials, its legacy reduced to a memory whispered among collectors. Walter Lange, the founder’s great-grandson, had long dreamed of bringing it back. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, he saw his chance. He had passion, but passion alone could not rebuild a brand from nothing. What he needed was strategy, capital, and vision.

Enter Blümlein. A fellow German, he carried the conviction that his people could face the worst odds through discipline, rigor, and a belief in excellence. Where others saw a romantic but impractical dream, he saw an opportunity to write a new chapter for German watchmaking. Together, Lange and Blümlein forged a partnership of heart and mind: Walter bringing heritage and legitimacy, Blümlein providing structure, daring, and the ability to rally investors, designers, and watchmakers around a clear purpose.

The result stunned the watch world. In 1994, A. Lange & Söhne unveiled its debut collection: the Lange 1, the Arkade, the Saxonia, and the Tourbillon Pour le Mérite. The Lange 1, with its asymmetric dial and outsized date inspired by Dresden’s Semper Opera clock, became an instant icon. “It was like nothing else,” one collector later recalled. “You didn’t just see the time—you saw an idea.”

And Lange didn’t stop there. In 1999 came the Datograph, a chronograph whose movement was so breathtakingly executed that it redefined what modern watchmaking could be. Independent master Philippe Dufour famously called it “the best chronograph ever made.” For many, it was proof that Glashütte was not just back on the map—it was setting the standard.

Blümlein had done more than revive a dormant brand. He had restored German watchmaking to world prestige, making A. Lange & Söhne not merely a survivor of history, but a peer—and in some eyes, a rival—of Switzerland’s finest maisons.

The Man Behind the Watches

Blümlein was not easy. Colleagues describe him as demanding, even intimidating, but always inspiring. Walter Lange called him a “universal genius… a technician, a perfectionist, and an extraordinary marketing strategist.”

He also knew how to mentor. Maximilian Büsser, later founder of MB&F, remembers Blümlein telling him: “Creativity is not a democratic process.” It was a lesson in the necessity of conviction.

He understood watches as both machines and messages. He could talk about balance springs in one meeting and advertising slogans in the next. Few leaders have ever spanned both worlds so effortlessly.

The Richemont Chapter—and a Sudden Ending

In 2000, Blümlein engineered one of the biggest deals in watch history: the sale of LMH—comprising IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and A. Lange & Söhne—to Richemont for over CHF 3 billion. Richemont wanted the brands, yes, but more importantly, they wanted him.

Tragically, just a year later, in October 2001, Blümlein died unexpectedly at 58. The industry, still basking in the renaissance he had set in motion, was stunned.

His Legacy Ticks On

Two decades later, his influence is everywhere.

- IWC remains the watchmaker of engineering elegance.

- Jaeger-LeCoultre is once again the Grande Maison.

- A. Lange & Söhne is revered as one of the world’s top manufactures, producing pieces like the Lange 1 and Datograph that collectors dream about.

But beyond the brands, his true gift was reframing what a mechanical watch meant. He made them into objects of culture, symbols of heritage and ingenuity.

Look at a Reverso, a Da Vinci Perpetual Chronograph, or a Lange 1 today, and you don’t just see a watch. You see a story—a belief that even in an age of quartz and smartphones, the mechanical heartbeat still matters.

A Golden Age Born of Vision

Günter Blümlein may not have been a watchmaker in the traditional sense, but he was a builder of futures. He took three struggling brands and gave them new souls. In the process, he pulled the entire mechanical watch industry out of crisis and into a golden age.

His legacy is a reminder: in watchmaking—as in life—vision, courage, and respect for tradition can reshape the world.

Article by Omar, founder of The Watch Curators