Editor's Note

In the first part of this article, we have covered how the invention of the Quartz was movement was like the opening of a Pandora's box for the Swiss Watch industry. The cat was out of the bag, and it caused mayham that lasted a little over two decades and redefined centuries old industry.

In this second part, we shall see how the phoenix rose from the ashes and meet some of the heroes that made it happen.

Part II – The Resurrection

The Secret in the Attic

In the mid-1970s, as corporate edicts came down to scrap mechanical tooling, a quiet act of rebellion unfolded in Le Locle. At Zenith, management had decreed that the factory's chronograph machinery be dismantled and sold for scrap.

The mechanical chronograph, they reasoned, was finished. Quartz had rendered it irrelevant. Why waste precious factory space on presses, cams, and dies that would never again see use?

But one man couldn't accept this verdict. Charles Vermot, a master watchmaker, began a clandestine operation. Working nights and weekends, he methodically labeled every tool, catalogued every drawing, and hauled the heavy machinery up narrow stairs to a dusty attic. Then he bricked them behind a false wall. For years, no one knew they existed.

It was an act of quiet defiance that would change horological history. When Rolex came knocking in the 1980s, desperately seeking a reliable automatic chronograph movement, Vermot's hidden treasure trove allowed Zenith to resurrect the legendary El Primero. What management had condemned to death, one man's stubborn faith had preserved for posterity.

The Contrarian's Gambit

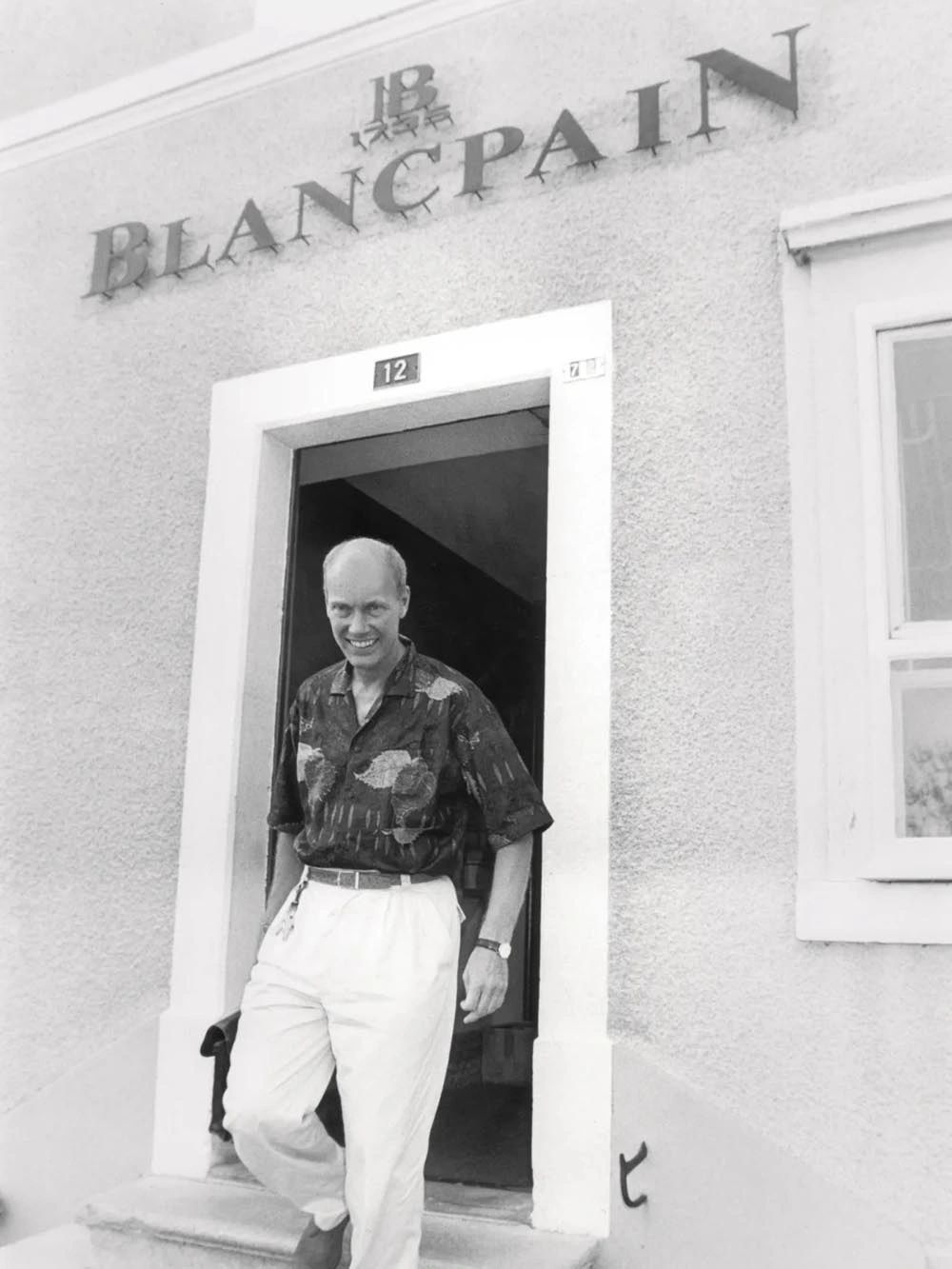

While most maisons scrambled to release quartz models, one tiny brand made a different bet. In 1983, Jean-Claude Biver and Jacques Piguet acquired Blancpain—a dormant name from horology's golden age—for what amounted to pocket change.

Their marketing strategy was as bold as it was audacious:

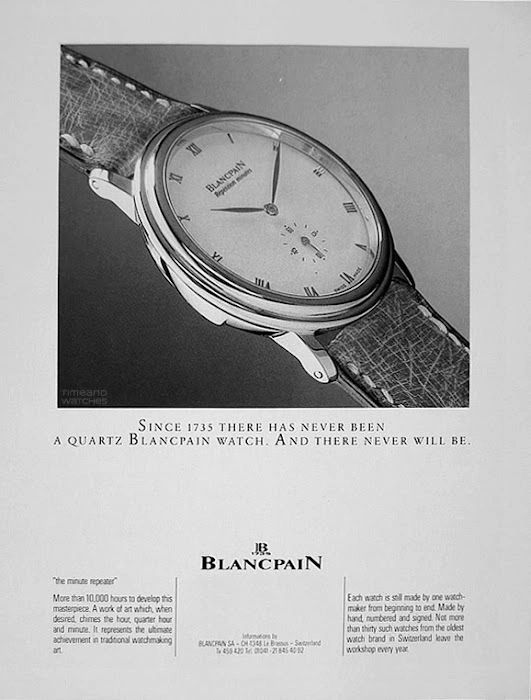

"Since 1735, Blancpain has never made a quartz watch. And never will."

In an era when everyone else seemed ashamed of mechanical watches, Blancpain transformed defiance into luxury positioning. They produced small quantities of exquisite, complicated mechanicals, and buyers—starved for romance and exclusivity in a digital world—took immediate notice. Blancpain's renaissance proved that emotion could triumph over pure efficiency, and it planted the seeds for an industry-wide revival.

Even Rolex Blinked

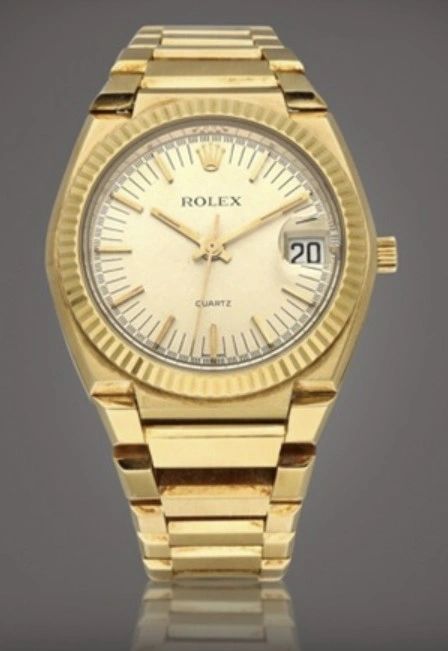

Even Rolex, the most conservative of Swiss houses, hedged its bets. In 1977, the company introduced the Oysterquartz, a sharp-edged, integrated-bracelet design very much of its angular era. Rolex built it to exacting Rolex standards: solid, precise, and produced in deliberately limited quantities.

The Oysterquartz ran for more than two decades, finally discontinued in the early 2000s. But history has judged it less as a quartz triumph and more as an artifact of a cautious company testing unfamiliar waters while keeping its mechanical soul intact.

The Vanishing Generation

Meanwhile, the human cost grew ever steeper. By the early 1980s, Switzerland had lost nearly two-thirds of its watchmaking workforce. An entire generation of artisans trained to polish, regulate, and assemble intricate mechanical movements found themselves obsolete overnight.

Consider the Valjoux 7750, an automatic chronograph movement introduced in 1974. Market conditions forced its shelving within a single year—there simply wasn't enough demand. But its designer, Edmond Capt, refused to let it die. Like Vermot at Zenith, he safeguarded the tooling and documentation through the dark years.

By the mid-1980s, when mechanical watches began their tentative return, the 7750 roared back into production. Today, it stands as perhaps the most widely used Swiss chronograph caliber in the world—a survivor that almost wasn't.

The Consultant's Revolution

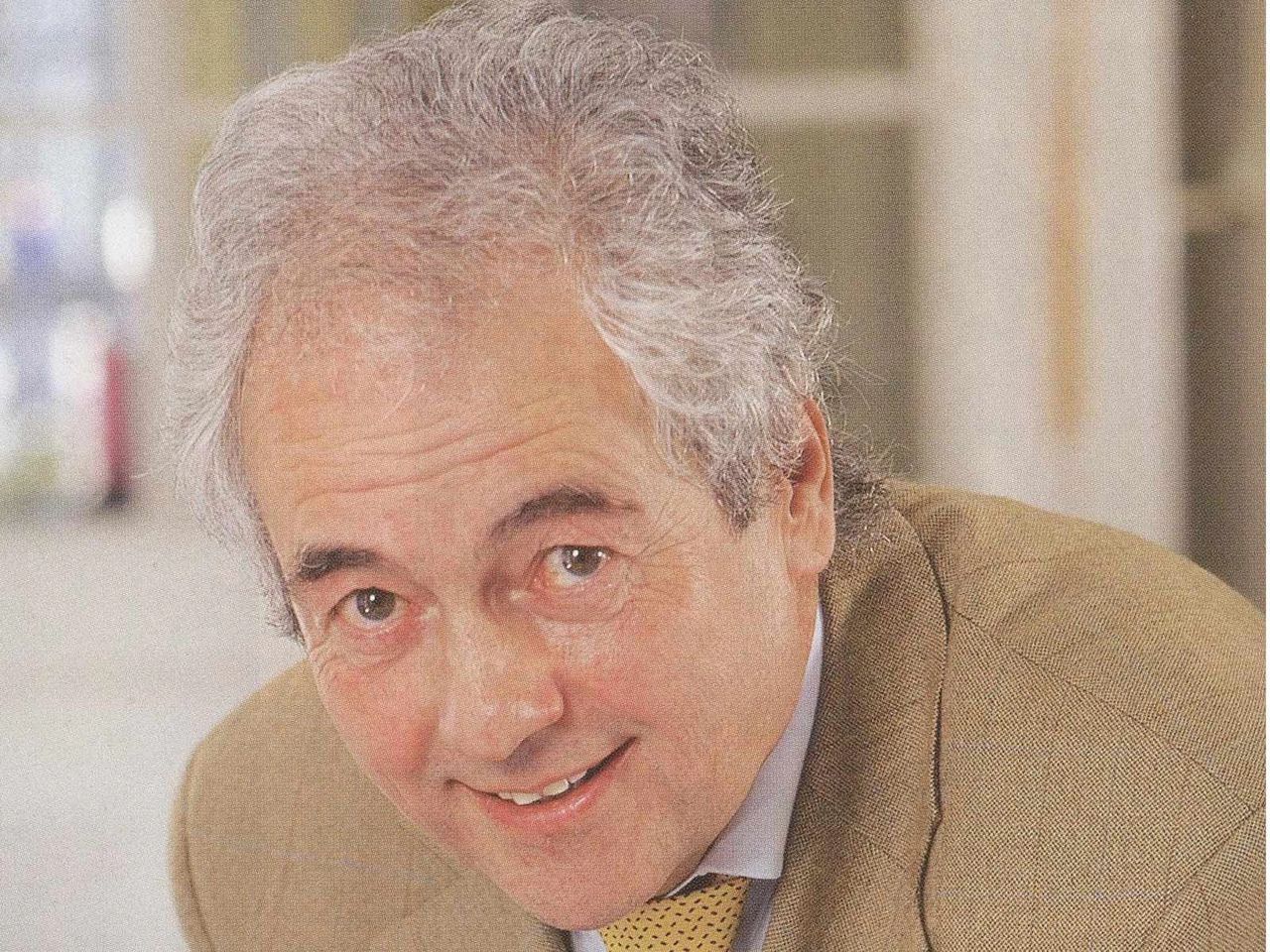

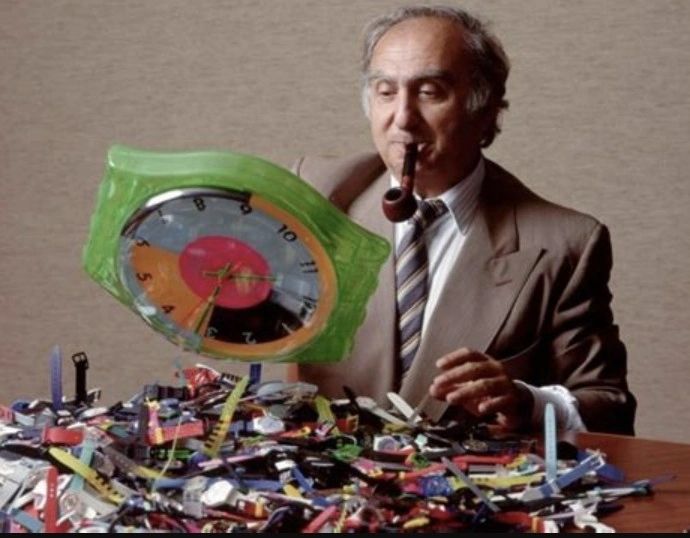

By 1982, Switzerland's two largest groups—SSIH (home to Omega and Tissot) and ASUAG (home to ETA and dozens of component suppliers)—were drowning in red ink. Desperate banks called in Nicolas G. Hayek, a Lebanese-born management consultant, to study the carnage and recommend solutions.

Hayek's prescription was radical surgery. First: consolidate the dying groups into one entity, eliminate redundancies, and centralize movement production under ETA. Second: automate ruthlessly, designing watches with fewer components and minimal hand labor. Third: stop competing with cheap Japanese quartz on price alone. Instead, reposition Swiss watches as objects of emotion, artistry, and social status.

In 1983, the world met his miracle cure: the Swatch.

Plastic Salvation

At first glance, the Swatch was almost insulting: a cheap, colorful, plastic watch. But beneath its playful exterior lay brilliant strategy. With just 51 components, assembled entirely by automated machinery, it delivered Swiss quality at mass-market prices. The whimsical designs transformed the humble wristwatch into a fashion statement.

The Swatch wasn't about superior timekeeping—it was about personal expression. And the world responded with unprecedented enthusiasm, snapping up millions of units. Those Swatch profits became the financial foundation for reviving Omega, Longines, Breguet, and Blancpain. Hayek's newly formed SMH (later renamed The Swatch Group) became the cornerstone of Switzerland's stunning comeback. In history's strangest twist, a cheap plastic watch had saved centuries of mechanical tradition.

Other resurrections unfolded brand by brand across Switzerland. Heuer, battered by the 1970s downturn, found salvation in 1985 through acquisition by Techniques d'Avant Garde (TAG).

The reborn TAG Heuer doubled down on motorsport heritage, produced reliable quartz chronographs, and slowly rebuilt its reputation. By the 1990s, TAG Heuer had successfully repositioned itself as the accessible face of Swiss luxury sports watches—a role it maintains today.

Quartz Evolves

Quartz technology didn't disappear—it matured and found its place. Grand Seiko's 9F calibers, launched in the 1990s, offered thermal compensation, extended battery life, and accuracy within ±10 seconds annually. Longines introduced V.H.P. (Very High Precision) quartz movements with similar capabilities.

Even in haute horlogerie, quartz carved out niches. F.P. Journe's Élégante featured a motion sensor that stopped the hands when unworn, conserving precious battery life—quartz engineering elevated to an art form. The division became clear: quartz had won ubiquity, while mechanical had won prestige. Both coexisted, serving fundamentally different human needs.

Hard-Won Wisdom

The Quartz Crisis left lasting scars—but also invaluable lessons:

- Technology waits for no one. The Swiss invented the quartz wristwatch but catastrophically underestimated its disruptive power.

- Generosity can backfire. CEH's open-patent policy handed competitors the tools to surpass their creators.

- Emotion trumps accuracy. Once quartz made perfect timekeeping affordable, mechanical watches became about romance, artistry, and personal identity.

- Strategic consolidation saves industries. Without Hayek's bold restructuring, Swiss watchmaking might never have recovered.

The Pendulum Swings

By the mid-1990s, cultural winds had shifted dramatically. Collectors rediscovered mechanical marvels with renewed passion. Auction houses reported record-breaking prices for vintage Patek Philippes and Rolex Daytonas. The steady tick of gears and springs became a powerful symbol of permanence in an increasingly digital world.

The Quartz Crisis hadn't killed traditional watchmaking—it had forced a fundamental reinvention. A mechanical watch today isn't about superior accuracy; it's about expressing identity, values, and connection to centuries of human craftsmanship.

Consider the survivors: Zenith, Blancpain, Omega, TAG Heuer, Lange. Remember the stubborn individuals who refused to surrender: Charles Vermot in his secret attic, Edmond Capt protecting the 7750, Jean-Claude Biver daring to say "never will." The ticking of a mechanical watch today carries meaning far beyond mere timekeeping. It is the sound of defiance, of survival against impossible odds, of ancient craft that stared extinction in the face and chose to endure.

Epilogue

The Quartz Crisis remains the most dramatic chapter in watchmaking history (to date). It is ultimately a story of hubris and humility, of technological disruption and human resilience, of a tiny crystal that nearly silenced centuries of tradition—and of the dreamers who refused to let time itself be forgotten. In saving mechanical watchmaking, these rebels didn't just preserve an industry. They proved that in our rush toward efficiency and perfection, there remains profound human hunger for beauty, complexity, and the irreplaceable touch of human hands. The mechanical watch survives not because it keeps better time, but because it keeps something far more precious: our connection to the patient artisans who, even in darkness, never stopped believing in the magic of gears and springs.

Time, as it turns out, was on their side after all.

Article prepared by Omar, Founder at The Watch Curators.