“Form follows function — but in horology, philosophy follows movement.”

Chronographs are among the most beloved complications in watchmaking — admired for their functionality, beauty, and the intricate choreography beneath their dials. But there’s a mechanical divide that defines how they come to life: modular versus integrated movements. Both measure elapsed time, but each tells a different story about engineering philosophy, manufacturing heritage, and the emotional feel of the pushers under your fingertips.

First things first: What is a Chronograph?

A chronograph timepiece is a watch with a built-in stopwatch function. Through a set of pushers and levers, it allows you to measure time intervals on demand — starting, stopping, and resetting with mechanical precision. Every press of a pusher sets off a miniature mechanical performance. The question to which this article responds is: how is that performance built?

Simply put, there are two ways:

- By adding the chronograph as a mechanical layer (That would be a modular chronograph), or

- By designing it into the movement from the ground up (That would be an integrated chronograph).

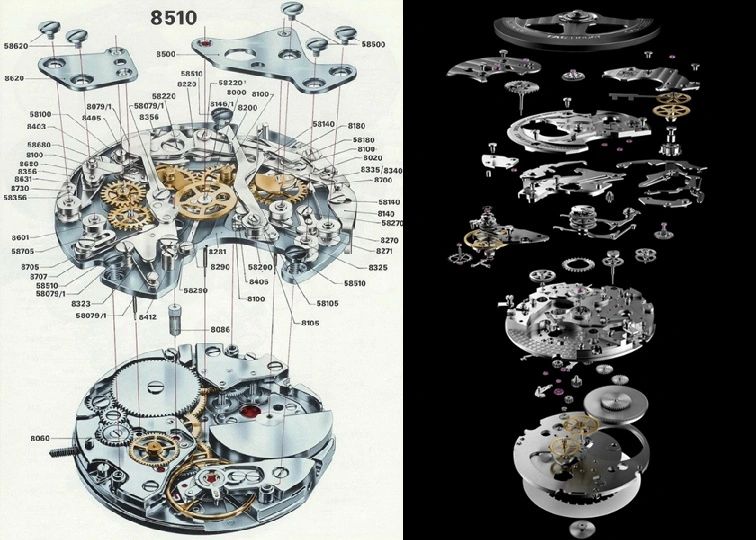

The Modular Chronograph

Think of the modular chronograph as a well-engineered add-on. It starts with a standard automatic or manual movement — called the base caliber — and adds a chronograph module on top. In watchmaking, the word modulerefers to an additional mechanical component, or set of components, that is almost useless on its own, but when mounted on top of a base movement - also known as the ébauche - to provide extra functions or complications. This is a solution often used to avoid the designing and development of a whole new movement from scratch. The result: a functional and reliable chronograph, built in layers like a mechanical sandwich.

How It Works

- The base keeps time.

- The module above manages the stopwatch function.

- Energy transfers from base to module through a coupling gear.

Using the modular approach to a chronograph certainly has advantages as well as drawbacks. Ultimately, it is the brand’s responsibility to figure out what they are comfortable with in terms of potential drawbacks when they make the choice of going for a Modular Chronograph instead of an Integrated one.

There seems to be four important advantages:

Flexibility: A brand may already have a solid and reliable base caliber or ébauche that they’d want to use.

Cost-effectiveness: The R&D cost to develop a Chronograph module – in terms of time and money – is certainly lower than tackling the daunting task of building an integrated Chronograph movement from the ground up.

Servicing: In this configuration, should there be a malfunction of the Chronograph, the module can easily be detached from its base caliber to be repaired separately.

Reliability: A module will have less parts than a whole integrated movement. Less parts means improved reliability

While the above is agreed and understood, each brand must keep in mind that a Modular Chronograph will come short on three topics where an integrated one will simply be superior:

Thicker watches: A stacked design will systematically add height to the whole movement, forcing the brand to manufacture thicker watches.

Asymmetry: The Chronograph function pushers will be directly linked to the module while the crown for winding and time adjustment will be linked to the base caliber. This means that the pushers will be slightly higher than the crown. The brand will then need to have some design gymnastics to do in order to reduce the visual impact on the overall aesthetic of the watch.

Prestige and market attractiveness: Most genuine die-hard watch collectors will always prefer an Integrated Chronograph. Most would consider the Modular approach to be a shortcut, not to say just a lazy attitude.

To put it simply, consider this: the modular chronograph is like adding an elegant annex to a well-built house — smart, efficient, but visibly and structurally uneasy.

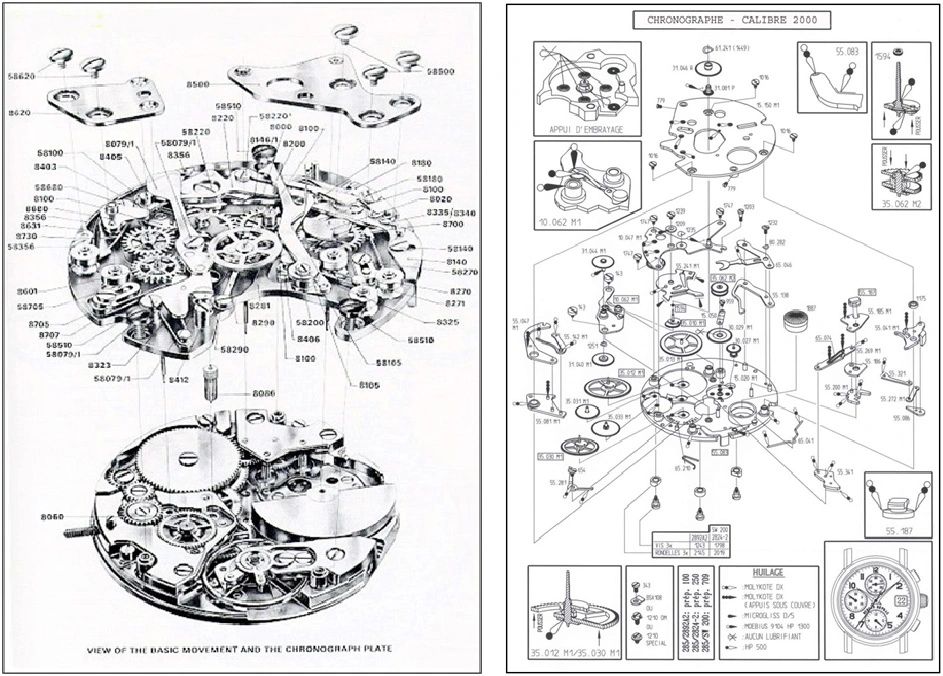

The Integrated Chronograph

By contrast, an integrated chronograph is pure horological artistry — conceived as a single, unified mechanism. Every component, from the escapement to the column wheel, is designed together. It’s the equivalent of a symphony written in one movement, not multiple acts stitched together. Some of the most famous Chronograph movements out there are always Integrated. The Zenith El Primero – around is 1969 – or the A. Lange & Söhne Datograph L951.6 are strikingly beautiful and mesmerizing, certainly favorites amongst collectors the world over.

The integrated movement approach will also have advantages and shortcomings. Again, it is up to the brand to decide which route makes the most sense for their objectives.

On the positive side of things, if a brand decides to go down the integrated approach, they’d be able to get:

A slimmer profile: Instead of stacking different elements, they will have an efficiently built single cohesive unit.

Energetic efficiency: A purpose-built integrated movement will have fewer friction points and a more efficient energy distribution system.

Symmetry: The watchmakers, while building the movement, will be able to align pushers and the crown perfectly.

Prestige: Making one’s own integrated chronograph movement is considered to be the hallmark of true mastery, gaining the respect and admiration of watch collectors and one’s peers.

These advantages may seem obvious, yet they are countered by two serious drawbacks:

Expensive: It is estimated that the development of an integrated Chronograph movement from scratch could take anywhere between 5 and 10 years of R&D. The price point of a watch then becomes much higher than that of a modular chronograph movement.

Servicing: Deep integration requires skill and time. Watchmakers must be specifically trained to be able to handle such movements.

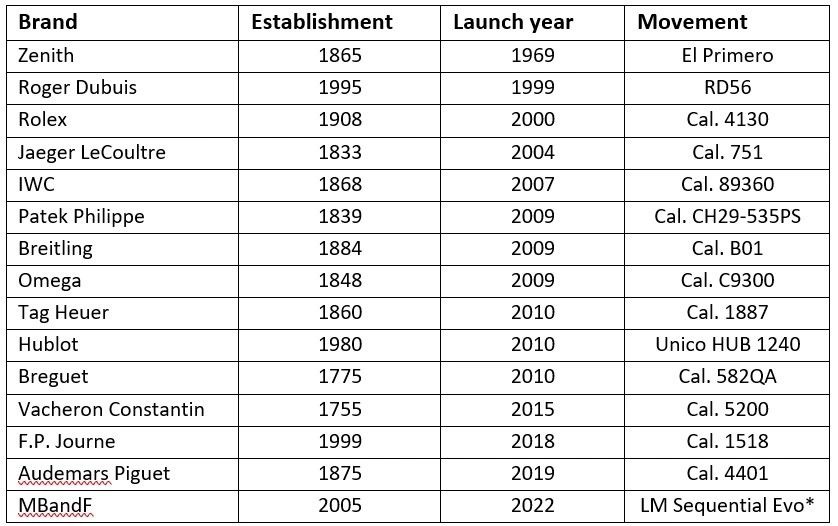

Understanding this, it is important to keep in mind that designing and manufacturing an integrated chronograph is a rite of passage for any serious watchmaker. While in today’s world watch lovers consider certain brands and manufacturers more prestigious than others, it is interesting to look at the table below, and notice the year of the brand’s establishment versus the moment they launched their own integrated chronograph movement.

MB&F itself has not developed a chronograph movement fully in-house. When it created its chronograph concept, the Legacy Machine Sequential EVO, it partnered with Stephen McDonnell, an independent Irish watchmaker. It is a true integrated chronograph, proprietary to, but not made in-house by, MB&F — rather, designed for them by Mr McDonnell. The LM Sequential EVO is notable for its “Twin Chronograph” system — two independent chronographs that can be operated separately or in sync — an innovation unmatched in the industry at the time of this writing.

In Part II, we shall cover the topic related to the Control aspect in Chronographs: Column Wheel vs Cam Lever.

Article prepared by Omar, Founder at The Watch Curators.