What makes mechanical watches so addictive isn’t just the romance of springs and gears—it’s what those parts conspire to do. In watchmaking, anything a movement does beyond displaying hours, minutes (and often seconds) is called a “complication.” Some are practical, like a second time zone for frequent flyers. Others could be perceived as poetic: chiming the time on demand or charting the moon’s slow drift across the night sky. This guide maps the landscape—what matters, how the mechanisms work, and what to keep in mind when considering complications for your collection.

What Counts as a Complication?

By convention, a simple three-hand watch is “time-only.” Add a date aperture, and you’ve crossed into complication territory. Notably, by this definition, certain features such as a Tourbillon or a Jumping Hour should not be considered as complications, and yet, they really and truly are. According to this definition, since the movement doesn’t add information beyond HMS (Hours-Minutes-Seconds), it does not qualify. Yet, the amount of ingenuity and the required technical expertise and prowess to develop and execute such features within a watch movement is certainly a lot more complicated than simply adding the date or day function. Accordingly, and for the sake of this article, we shall include these non-complication features as proper complications.

Everyday Workhorses: The “simple” complications

Not every complication needs to be exotic or theatrical. Actually, the most useful are those you’ll interact with daily, the quiet workhorses that make living with a mechanical watch more practical.

The Date is the most common. Whether it’s a small window at 3 or 6 o’clock – as you’d see in most watches with this function - or an oversized “big date”, as you’d see in the Lange 1, using two discs, it’s the first step beyond time-only. The latter – The Big Date – is in reality far more complicated to develop and manufacture than a “simple” date function.

The Day-Date watches (and their slightly fussier cousin, the triple calendar) are less common, and the most famous example is the iconic President’s Rolex Day-date. Besides the day of the week is indicated as well as the day. A triple calendar will even add the month. They’re undeniably charming, but the extra text can clutter a dial, and setting them takes some getting-used-to. If you rotate watches often, look for versions with clever pushers or straightforward manuals—it will definitely make your life easier.

The Power reserve indicators are another deceptively simple addition, especially on hand-wound watches. Think of it as a fuel gauge for your movement, telling you how much energy remains in the mainspring before the watch winds down. On an automatic watch, it is less critical since the rotor keeps things topped up, but it’s still deeply satisfying to see that needle swing from “empty” to “full” as you wind.

When considering these complications, here’s what to look for: a date that jumps crisply, corrector pushers that are discreetly integrated into the case, and a power reserve scale that’s intuitive at a glance!

The Time-Zone Family: For the globe-trotters

With the explosion of tourism in the twentieth century and the invention of air travel and telecommunication, watchmakers realized that certain information useful to travellers could be added onto existing movements. In today’s world, few complications are as practical as those built for travel.

The GMT (or dual-time watch) is the classic choice, but not all are created equal. There are two main types:

- Flyer GMTs (sometimes called “traveller GMTs”) let you adjust the local hour hand in one-hour jumps while the 24-hour “home” hand stays fixed. This makes them ideal for actual travel—your local time and date adjust seamlessly as you land in a new city. The very popular Rolex GMT Master II would fall into that category.

- Caller GMTs work the other way around: you move the 24-hour hand independently while the main hour hand stays put. These are perfect if you’re staying home but need to keep track of a colleague or loved one in another time zone. The Grand Seiko Elegance GMT is a great example!

Many GMTs also feature a rotating bezel—Consider the Rolex GMT Master II—which lets you track a third time zone with a quick twist. It’s a simple but clever layer of versatility.

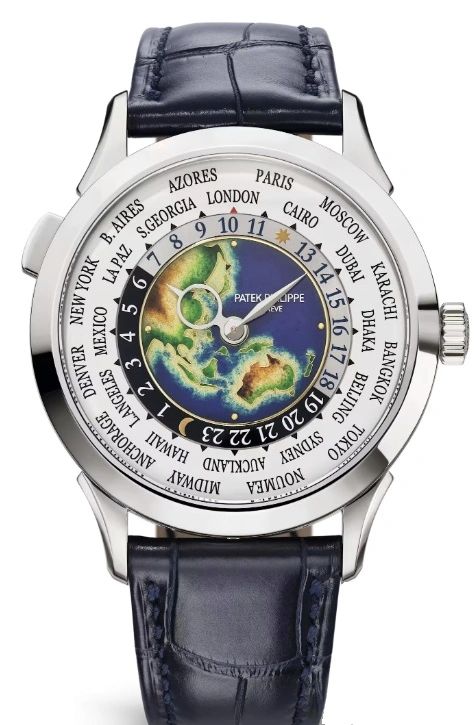

World Timers take the concept a step further. By combining a city ring with a 24-hour disc, they let you read the time anywhere on the globe at a glance. Born from Louis Cottier’s ingenious mid-century design, they still carry that jet-age glamour today—though you’ll need to remember that daylight saving quirks still require a bit of mental math. In the modern world, there are several countries and territories that have half-hour offsets (India, Iran, parts of Australia, etc…) that can’t be covered by this function. To the best of our knowledge, no watchmaker has yet figured out how to do that. A great example of a World Timer would be the beautiful Patek Philippe reference 5231G

What to look for: for frequent flyers, a flyer GMT with a date linked to the local jumping hour; for desk pilots, caller GMT is perfect. With world timers, legibility of the city ring and the day/night contrast on the 24-hour disc are everything.

Calendars, from Annual to Perpetual (and the Moon in Between)

If time-only watches are about the steady tick of the hours, calendar watches are about the messy reality of human timekeeping. The Gregorian calendar, with its irregular months and leap years, is full of quirks—and watchmakers have spent centuries figuring out how to squeeze that logic into a movement no bigger than a 19th century coin.

Complete or Triple Calendars are the entry point. They usually display the date, day, and month (often paired with a moonphase for extra charm). Practical, yes—but they don’t “know” which months are short, so you’ll need to step in five times a year, adjusting at the end of every month with fewer than 31 days. A great example of this would be Complete (or triple) calendar by MAGANA, Tribute to Liwa, a sport-chic easy-to-wear watch with a useful function.

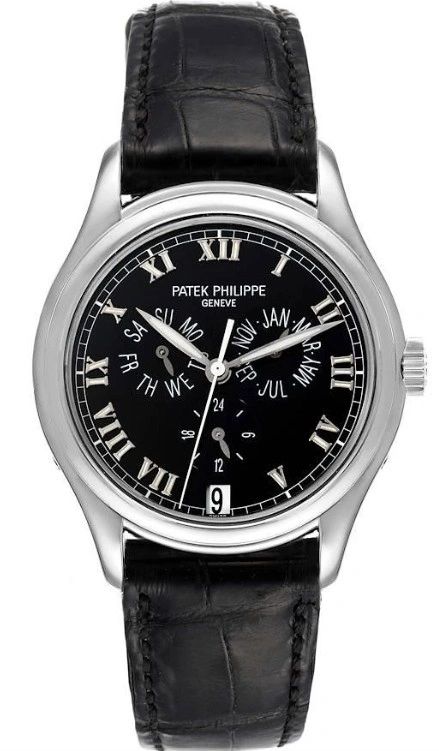

Annual Calendars were Patek Philippe’s gift to the modern collector in 1996: a mechanism smart enough to distinguish between 30- and 31-day months, needing correction only once a year at the end of February. The genius here is balance—most of the elegance of a perpetual calendar, but without the same fragility, thickness, or price tag. For many enthusiasts, it’s the perfect blend of practicality and poetry. The highly collectible reference 5035G by Patek Philippe is a great example, worth to be part of any decent collection.

Perpetual Calendars are where watchmaking becomes choreography. These mechanisms automatically account for leap years and irregular Februaries, correctly displaying the date until the year 2100 (an anomaly in the rules of the Gregorian calendar). At their heart is a cam – just like what you’d have in a car - that completes a full cycle every four years, storing the leap-year logic. Levers and feelers “read” the cam’s profile and command the date to jump forward by 28, 29, 30, or 31 days as needed. It’s a miniature ballet in brass, but a sensitive one—let the watch run down for weeks and you’ll spend a long evening with pushers, crown, and manual. Today’s watchmaker’s push the boundaries even further, just like the MB&F Legacy Machine LM Perpetual which is a brilliantely executed example of what a modern QP (Quantiéme perpétuel in French) should be

And then there’s the Moonphase, arguably the most poetic complication of them all – and most likely the least useful one today. A small disc, often decorated with starry skies and golden moons, tracks the lunar cycle. Most traditional designs use a 59-tooth wheel that advances once per day, coming remarkably close to the true lunar month of 29.53 days. The result? An error of about one day every two and a half years. High-end implementations add more teeth or gear refinements, stretching that accuracy to decades—or even centuries. Beyond the numbers, it’s about romance: a tiny night sky on your wrist. A beautiful example of this complication would be the Arnold and Son’s Perpetual Moon.

What to look for: Make sure to use correctors (or pin-pushers) that are safe and intuitive—some movements can be damaged if adjusted during the wrong hours. A clear leap-year display on perpetuals, so you don’t lose track of where the mechanism is in its cycle. On moonphases, discs with crisp printing, enamel, or even sculptural relief that turn a technical display into a work of art.

If your watch is part of a rotation and spends time off the wrist, an annual calendar often strikes the sweet spot between everyday convenience and horological poetry.

Article prepared and written by Omar, founder of The Watch Curators