Few figures in modern business history can claim to have (almost) single-handedly saved an entire national industry. Nicolas George Hayek, often remembered as the colourful and outspoken founder of the Swatch Group, did exactly that. In the early 1980s, when the Swiss watchmaking industry was in disarray—facing what many feared was terminal decline—Hayek stepped into the picture with vision, determination, and a flair for marketing unlike anything the industry had seen before.

Hayek did more than rescue Swiss watchmaking from collapse; he reinvented it. Through bold restructuring, innovative product development, clever branding, and a strategy of acquiring and reviving historic maisons, he turned a fragmented, defensive industry into a revitalized powerhouse. To appreciate the full magnitude of his impact, it is worth exploring the crisis he inherited, the steps he took, the acquisitions he made, the legendary watches he championed, and the enduring legacy he left behind.

The Quartz Crisis: Swiss Watchmaking on the Brink

To understand Hayek’s role, one must first revisit the “Quartz Crisis” of the 1970s and early 1980s. For centuries, Switzerland had been the uncontested leader in watchmaking, producing mechanical timepieces renowned for precision, craftsmanship, and design. Yet when quartz technology—pioneered in Japan by Seiko—arrived, the Swiss were slow to react.

Quartz watches were cheap, accurate, and reliable. The Japanese, alongside American firms like Timex, embraced the new technology and flooded the global market with affordable quartz watches. By the late 1970s, Switzerland’s market share had plummeted. Where it once controlled over half of the world’s watch exports, that number collapsed to less than 15%. Tens of thousands of jobs vanished, and centuries-old maisons shuttered.

In 1982, two of Switzerland’s largest watch groups with brands like Omega, Tissort or Longines — ASUAG and SSIH — teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Banks, heavily exposed to these companies, sought outside help. They hired a Lebanese-born management consultant named Nicolas Hayek. What he found was a national treasure on life support.

Nicolas Hayek: Outsider with a Vision

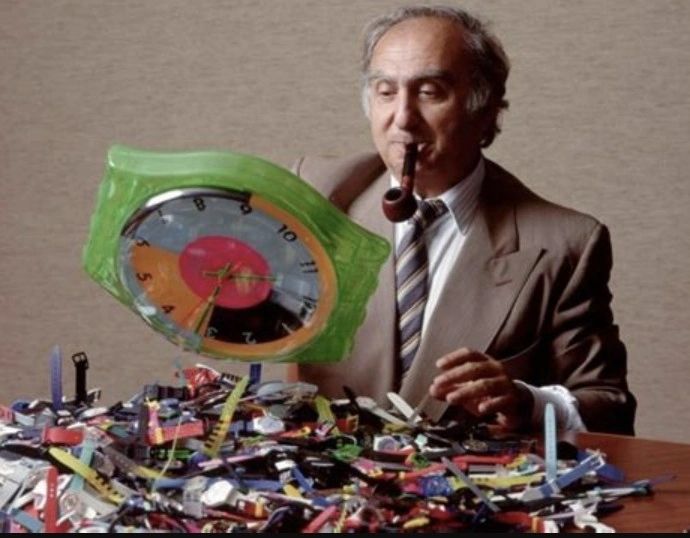

Hayek was not Swiss by birth. Born in Beirut in 1928, he moved to Switzerland in 1951 and built a successful consulting firm, Hayek Engineering. Known for his sharp analysis and decisive style, he was also charismatic and larger than life—often photographed with a cigar in hand and Swatch watches stacked on his wrists. When Swiss bankers asked him to restructure ASUAG and SSIH, they expected a surgeon’s report recommending liquidation. Instead, Hayek saw opportunity.

He quickly recognized that Switzerland’s watch crisis was not about lacking technical know-how, but about poor strategy, sluggish branding, and bloated inefficiencies. The country still had the skills, the heritage, and the mystique. What it lacked was leadership and boldness.

Hayek proposed merging the two groups, cutting redundancies, modernizing production with automation, and launching a new product that could compete with quartz watches on price and personality—without abandoning Swiss identity. This plan birthed SMH (Société Suisse de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie) in 1983—the precursor to the Swatch Group. The new product was none other than the SWATCH watch.

The Swatch Revolution

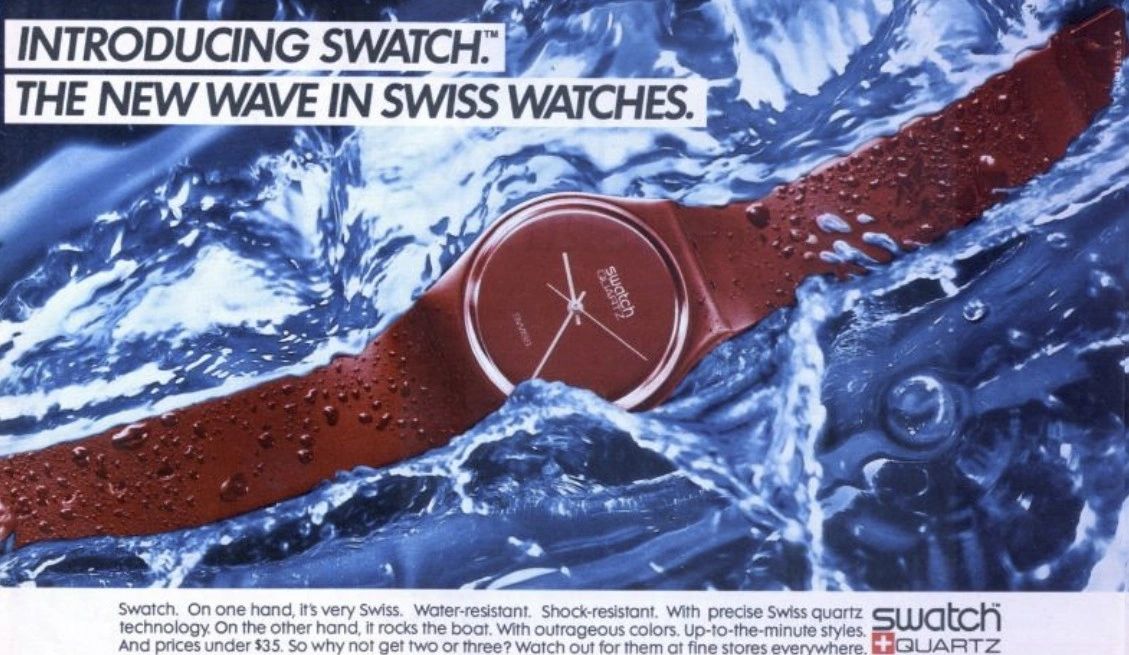

Central to Hayek’s turnaround was a new product: the Swatch watch. Even its name was clever—a fusion of “Swiss” and “watch,” both patriotic and catchy. Introduced in 1983, it was everything traditional Swiss watches were not. Plastic, colourful, playful, affordable—priced in the low tens of dollars. Instead of trying to beat Seiko at accuracy, Swatch redefined the category: watches as fashion, as fun, as emotion.

By reducing components to just 51, Swatch made watches cheaper and faster to produce, while marketing made them desirable. Artist collaborations, limited editions, and bold advertising transformed Swatch into a cultural phenomenon.

The watch was a hit, but perhaps even more impressive was what Hayek did with its profits. Rather than simply banking them, he reinvested into reviving the industry’s crown jewels. This pattern—using Swatch to bankroll heritage brands—was the heart of his strategy.

Hayek himself embodied the irreverence of the brand. At public events he would stack multiple Swatches on his wrists, half to provoke the conservative Swiss elite, half to demonstrate his point: watches were no longer just tools, they were self-expression. He once quipped that the initials of SMH, the holding company, stood not for “Société Suisse de Microélectronique et d’Horlogerie” but for “Sa Majesté Hayek”—His Majesty Hayek. Behind the bravado was a deep conviction that Switzerland could reinvent itself.

Acquiring the Icons: When, How, and How Much

As Swatch grew, Hayek turned his attention to heritage. His philosophy was clear: mass-market success should fuel the resurrection of prestige maisons.

- Blancpain & Frédéric Piguet: In 1992, Hayek acquired Blancpain and its movement maker Frédéric Piguet for CHF 60 million. Jean-Claude Biver, who had revived Blancpain in the 1980s with little more than passion and grit, initially resisted Hayek’s empire. Yet eventually, the two men worked together—Biver even taking charge of Omega. It was a pivotal partnership, blending Hayek’s resources with Biver’s marketing genius.

- Breguet: In 1999, Hayek purchased Breguet from Investcorp, a Bahrain-based investment group. He treated it as the crown jewel of the Swatch Group, restoring workshops, emphasizing Abraham-Louis Breguet’s legacy, and positioning the brand at the very top of haute horlogerie.

- Glashütte Original: In 2000, Hayek expanded beyond Switzerland, acquiring Glashütte Original in Germany. It was a move that mirrored what Günter Blümlein had achieved with A. Lange & Söhne: reviving German watchmaking’s prestige alongside its Swiss counterpart.

Other maisons—Omega, Tissot, Longines, Hamilton, Jaquet Droz, and more—were already part of ASUAG or SSIH and came into the Swatch Group via the merger. Hayek revitalized each, repositioning Omega through storytelling (space exploration, Bond, Olympics), Longines through elegance, and Tissot as accessible Swiss heritage.

The Marie-Antoinette Pocket Watch: A Legend Reimagined

Perhaps nothing captures Hayek’s reverence for history better than his decision to recreate the most legendary timepiece ever built: Breguet No. 160, the “Marie-Antoinette.”

Commissioned in 1783 for the doomed Queen of France, this pocket watch was to include every known complication and use only the finest materials. It was not completed until 1827, long after both the Queen and Abraham-Louis Breguet had passed. Over the years it passed through collectors before settling with the Salomons family in London. The watch No 160 – the Marie Antoinette - along with more than 50 other Breguet watches and a collection of Islamic art were donated to the L.A. Meyer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem in the 1970’s. Sadly, but it certainly enhanced the legendary status of the relic, it was stolen in 1983.

In 2004, while the original was still missing, Hayek ordered Breguet’s watchmakers to reconstruct it from surviving drawings and archives. After four years of painstaking work, the replica—Breguet No. 1160—was unveiled in 2008. For Hayek, this was not about selling a product, but about showing that the spirit of genius was alive within his group. When the original resurfaced in 2007, the project took on an even more legendary aura.

Parallel Paths: Hayek and Günter Blümlein

While Hayek was rescuing Switzerland’s industry, another outsider was writing his own chapter. Günter Blümlein, a German engineer, led the revival of IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and A. Lange & Söhne.

Though there is no evidence of a close collaboration, the two men operated in the same rarefied circles. Both were non-Swiss, both were visionaries, and both understood that watchmaking’s power lay as much in storytelling and heritage as in mechanics. Hayek built a conglomerate anchored by Swatch; Blümlein rekindled the soul of maisons. Together, they ensured mechanical watches were not relics of the past, but symbols of culture.

Legacy and Impact

Hayek died in 2010, suddenly, at his office desk. True to form, he was still working at full speed in his eighties. His legacy is monumental. The Swatch Group remains the world’s largest watch company, spanning entry-level Swatch to haute horlogerie icons like Breguet and Blancpain.

But Hayek’s true achievement is cultural. He preserved dozens of historic names not just by acquiring them, but by breathing new life into them. He proved that mechanical watches—once written off as obsolete—could thrive in a quartz world. He showed that fun and fashion could sit alongside tradition and craftsmanship.

Perhaps most importantly, he believed watchmaking was a national treasure, and he fought to keep its soul Swiss. From cigars and quips to bold deals and impossible projects, Nicolas Hayek left the industry not only richer, but more confident.

The next time you strap on a Swiss watch—whether a playful Swatch, an elegant Longines, or a regal Breguet—remember the man who made sure that centuries of tradition did not vanish into history. Hayek was not Swiss by birth, but he became one of Switzerland’s greatest champions. His legacy, ultimately, is time itself.

Article prepared by Omar, Founder at The Watch Curators abraham louis breguet