The Origin of "Calendar"

The word "calendar" derives from the Latin calendarium, meaning "account book" or "register," which itself comes from calendae, the term for the first day of the Roman month when debts were due. Ancient Romans used calendae to mark the start of lunar months, tying timekeeping to economic and religious cycles. This etymology reflects the calendar’s role as a tool for organizing time, a concept that evolved from simple lunar observations to the sophisticated systems we use today.

A Global Standard

Across the globe, nearly everyone can tell you what day it is, and in almost every language, June—whether Juin, Juni, or Junio—is universally recognized as the sixth month of the year. This global harmony in timekeeping seems natural today, but it took millennia to achieve. Let’s explore how humanity developed this synchronized system for tracking time.

Why Calendars?

Modern humans, Homo sapiens, emerged around 300,000 years ago, coexisting with species like Homo neanderthalensis. Around 30,000 years ago, Homo sapiens began noticing the regular movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, connecting these celestial patterns to the seasons. Unlike earlier humans who recognized day and night, Homo sapiens understood that seasons recurred predictably, influencing food availability.

Evidence of early farming, discovered in 2015, dates back approximately 23,000 years, aligning with the period when Homo sapiens and Neanderthals coexisted. This agricultural revolution likely gave Homo sapiens an edge, enabling them to outcompete Neanderthals by cultivating food rather than relying solely on hunting and gathering. By linking celestial movements to seasonal cycles, Homo sapiens laid the foundation for calendars, taking control of their food supply and destiny.

Early Calendars

A calendar is an organized system for measuring and tracking time. Around 3300 BCE, during the Bronze Age, the first calendars emerged, primarily lunar, based on the Moon’s phases. Each civilization adapted these systems for political, economic, or religious purposes. In Ancient Egypt, priests gained prestige by observing the star Sirius, which rose just before dawn, signaling the Nile’s annual flooding—a critical event for agriculture. This connection between astronomy and timekeeping was a guarded secret, not common knowledge 5,000 years ago.

The earliest known calendar, the Sumerian calendar, divided the year into months starting with the new crescent moon. The Babylonians adopted a similar lunar system but later incorporated solar observations, including Sirius, transitioning to a lunisolar calendar. Lunar calendars, still used in some cultures (e.g., the Islamic calendar), have a key drawback: a lunar year of about 354 days (12 months of roughly 29.5 days) is 11–12 days shorter than a solar year, causing months to drift relative to the seasons. For example, in the Islamic calendar, Ramadan shifts through the seasons, making fasting easier in winter’s shorter days than in summer’s longer ones.

To address this, some civilizations, like those in Mesopotamia and Republican Rome, used lunisolar calendars, adding an extra month periodically to align with the solar year. The Jewish calendar still employs this method, adding a thirteenth month, Adar II, seven times in a 19-year cycle to keep holidays like Passover in spring.

The Egyptians, leveraging their Sirius observations, developed a solar calendar with twelve 30-day months plus five extra days, totaling 365 days. This was more accurate than lunar calendars but still drifted slowly because it didn’t account for the solar year’s true length of approximately 365.25 days, causing a one-day lag every four years.

Solar Calendars

In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar introduced the Julian Calendar to the Roman Empire, advised by the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes. This calendar abandoned the lunar system, adopting a 365-day year with an extra day added to February every four years (leap year) to account for the solar year’s additional six hours. The Julian Calendar spread through the Roman Empire and later Christendom, becoming the standard for centuries.

However, the Julian Calendar overestimated the solar year by about 11 minutes annually, leading to a drift of roughly one day every 128 years. By the 16th century, this misalignment caused the spring equinox, critical for calculating Easter, to shift from March 21. Easter, symbolizing Christ’s resurrection and the triumph of light over darkness, was meant to align with the equinox.

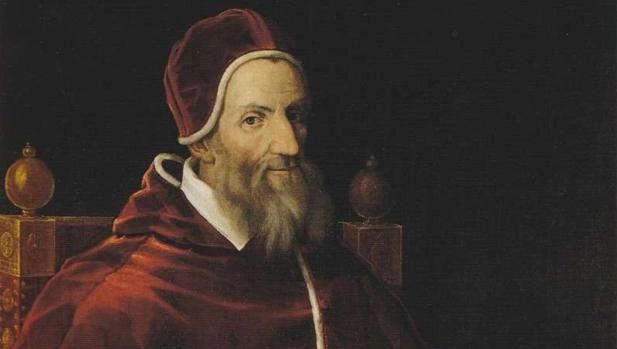

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII, advised by astronomer Aloysius Lilius, introduced the Gregorian Calendar to correct this. The solar year was refined to 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds. To realign the calendar, 10 days were skipped in October 1582, and a new leap year rule was established: a year is a leap year if divisible by 4, except for century years, which must be divisible by 400. This made the calendar far more accurate, losing only one day every 3,226 years.

The Gregorian Calendar faced resistance due to religious divisions in Christendom. Catholic nations adopted it immediately, while Protestant and Orthodox regions delayed, some until the 20th century, creating temporary calendar disparities across Europe.

Today, the Gregorian Calendar is the global standard, harmonizing timekeeping worldwide and ensuring that June remains the sixth month, no matter where you are.

Article written by Omar, founder of The Watch Curators.